I was working with Miguel in EU 12. This unit and EU 1 (finished shortly thereafter) were the only two units still digging although not necessarily finding many artifacts. EU 12 was an interesting unit for we were convinced that we had hit sterile soil, though the soil was not the brownish-orange subsoil we had found in the other units.

With a little further digging, we found our answer. As the blog related earlier, a dark stain appeared in the northeast corner of our presumed sterile soil (Image 1). This stain became Feature F and yielded the most amount of artifacts for the unit, including a fragment of a George Bauernschmidt bottle (similar bottle fragments from this brewery were found the last two years in Texas and even at the Irish Shrine!)—it must have been a popular local beer. The feature also included a porcelain cleat (for anchoring electrical wire), other ceramics, and a foil wrapper (Image 2).

IMAGE 1: Feature F- Dark soil stain in EU 12

IMAGE 2: Artifacts from Feature F

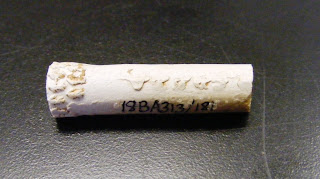

Before proceeding further, we made a planview map of Feature F in order to identify the dimensions of what and where we were digging. As we continued excavating down into the feature, the stain began to spread out into the rest of the unit. This soil layer was obviously a disturbed historic layer because of the quantity of artifacts and their position within the unit. For instance, the artifacts were mainly from the late nineteenth century (such as a pipe stem with the word [GL]ASGOW), but some of the artifacts were twentieth and late twentieth century— suggesting a mixing of soil layers or an intrusion into an existing soil layer (Image 3).

IMAGE 3: Pipe stem, glass, and ceramics

Below this dark soil layer sat a lighter soil layer with coal and limestone and thick lenses of charcoal. While no modern artifacts were found, a large piece of a grey salt-glazed stoneware crock was found as well as a pipe stem and a blue transfer-print whiteware piece (Image 4). Of course, by the time we had excavated a portion of this layer, the day was over. Yet the large piece of a crock (the largest artifact we had this year) and the absence of modern material suggests this could be an intact historic ground surface from the nineteenth century. The subsequent layers above could have been fill or much later activities, as the presence of a modern foil wrapper suggests. Even more exciting, the charcoal lenses could be associated with the burning of the residence in the 1890s? Still, we only had a few burned artifacts in this soil layer or in the other soil layers. We will have to clean and examine these artifacts in the lab to see if they show signs of exposure to high heat.

IMAGE 4: Grey salt glazed stoneware crock, ceramics, and other artifacts

On Monday, Paul and Peter came back and excavated EU 12 and quickly exposed the brownish-orange subsoil. After digging into this soil just to make sure it was sterile, Paul and Peter mapped the unit’s walls. By the end of a nice hot summer day, they had backfilled the unit and the excavation was officially over.

The final week of the field school was spent in the lab— where the real works goes on to make sense of the excavations and understand the artifacts in their contexts. Let me explain a little further. Artifacts are identified and described in depth in the lab. This level of the analysis allows us to compute quantity, affiliation, and possibly dates of when the artifacts were made and/or commonly used. Armed with this knowledge, we hypothetically can place the artifacts back in their excavation context or soil layers to understand where and how they were deposited in the ground. For instance, if a plastic wrapper was found in a soil layer below a soil layer with a pearlware ceramic dish, then we know that soil layer with the pearlware dish was deposited or modified fairly recently.

Artifact affiliation and context also aids in comparing and understanding the artifacts found at the entire site. For example, artifacts found in similar soil contexts but in different units likely found their way into the ground in a similar manner around the same time period. Thus, we can figure out what is happening over time at the site, and eventually piece together the lives of the inhabitants of Texas— our ultimate goal. Without these scientific methods, we are just simply looking for cool things and can never understand who was using them and why.

Working in the lab is a great relief for some, including myself. This field school has been a great experience. I personally have learned what I enjoy and what I would rather not do. The field school has been invaluable in helping me find the direction I want to take with archaeology. As a collective, I think we all enjoyed the field school and have learned a great deal! Thank you Dr. Brighton.

Now for me, I am not done yet. I have begun the accompanying lab portion of the summer session. This three-week class is going to work on washing, cataloging, and labeling the artifacts from the 2010 and 2011 Texas Field Schools. We are also going to be entering the data into a computer spreadsheet program to allow us to summarize our findings and to begin to analyze them closer.

Today was a rewarding day because Rachel and I finished cataloging the final artifacts of the 2010 Texas Field School (Image 5). We are now going to start washing the artifacts from this year’s field season. Once all the artifacts have been washed we will start the process of labeling and cataloging again! And so goes life in the archeology lab…

IMAGE 5: Erika working in the lab and boxes from three years of excavation at Texas

Erika Kruse

July 18, 2011