Last week working in the lab, the students finished labeling artifacts from the 2009 Field School in Texas, Maryland. With at least 50,000 artifacts, it really did take that long!

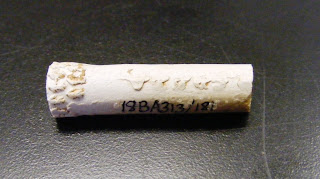

Currently, the students are working on labeling and cataloging artifacts from the 2010 Field School. Artifacts, such as the pipe stem, ceramics, cut nail, and writing slate and pencil depicted in Image 1, come in from the field dirty and grouped only by soil layer and unit. After a gentle washing and drying, artifacts are painted with a fine strip of acrylic, then the site number and lot number (a catalog number) is written on each artifact so that they can always be identified by their context (Image 2), even during vesselization (where pieces from the same artifact are put back together). Though tedious, putting artifacts back together allows us to understand exactly what and how much of something we have. Also, we can attempt to figure out how and when an artifact made its way into the ground by studying its parts and where they were located in the ground. Finally, a second layer of acrylic is applied to keep the site number and lot number from wiping away (Image 3).

Image 1: Artifacts (a pipe stem, ceramics, a cut nail, and a writing slate and pencil) recovered in the field

Image 2: Katie writing on an artifact in the lab

Image 3: Smoking pipe stem labeled with site and catalog number

After labeling, we are faced with the task of cataloging or inventorying (Image 4). When cataloging artifacts, students write down the type of material, its function, its form, any decorative qualities, if its whole or fragmented, if it contains any marks, and the finally the quantity. For example with a beer bottle, you would describe the type of glass (brown), then continue to list its qualities: its decoration (embossed), its category (kitchen), its function (alcohol), and its form (a bottle). If the artifact is whole you can catalog it as whole, but it is more common to log fragmented artifacts, which in the case of glass, can be divided into body, base, or lip pieces. Also, students can find maker's marks on the base of the bottles. These symbols or letters can help identify the company that made the bottle, narrowing down the time frame from which the bottle could come from as well as the location of manufacture.

Image 4: Erika cataloging a ceramic sherd with a Flow Blue decoration

We have been cataloging lots of brown bottle glass recently, as well as some clear bottle glass and window glass. We have also been cataloging lots of whiteware, specifically tableware, some of which is transfer printed with floral designs. We have also found some stoneware, yellowware and redware. In many cases, the artifacts are so small that vessel form cannot be discerned— perhaps vesselization can help us later in this regard.

Working in the lab can be tedious at times, yet, unlike working in the field, we can examine the artifacts more carefully and fully. With various references, we can look up details about them, like if a glass bottle has a brandy or a crown cap finish— giving us clues to their contents and uses. These details are interesting because the lab is not only where each artifact can be examined closely, but where all the artifacts can be studied together as an assemblage. When all the artifacts are entered into a spreadsheet, we then can begin to figure out the nature of the site, who the people were, how they lived, and numerous other exciting questions. For now, we still have a lot of work to do.

Rachael Pacella

June 28,2011

No comments:

Post a Comment